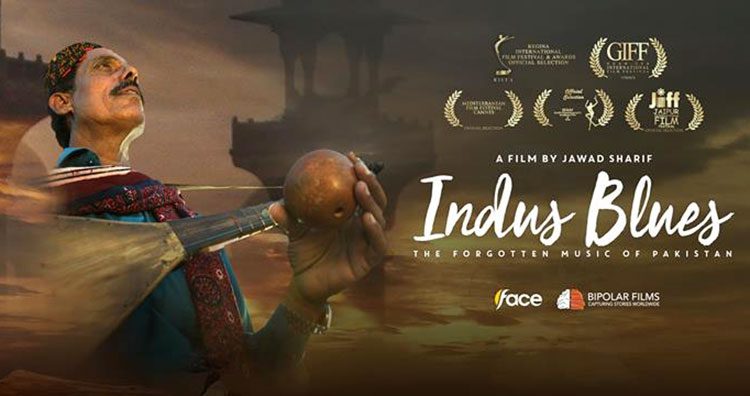

A modern day travelogue, accompanied by an accurate and objective ethnographic account, the documentary Indus Blues provides any viewer with a roadmap of the musical traditions of Pakistan. On June 14, 2019 premiering for the first time in Pakistan, Indus Blues opened to a full house at Pakistan National Council of the Arts (PNCA) in Islamabad. Directed and produced by Jawad Sharif, it details the personal lives, experiences and raw emotions of Pakistan’s folk and classical musicians and the legacies of ancient instruments including the Raanti, Sarangi, Suroz, Balochi Banjo, Chardha, Murli Been, Alghoza, Boreendo and Sarinda.

The documentary presents multiple perspectives, ranging from regional identities and contrasting topographies, to generational communities that live by the rhythm and frequencies of these instruments. It is a conversation with the musicians and craftsman who make these instruments and live with the knowledge that these traditions are dying out. They are underappreciated, overlooked and even ostracized for their musical passions. We intimately view their struggle, of devoting entire lives to the soulful and selfless act of performance. The documentary presents a sad reality that this cultural heritage will fade away with these unsung heroes, unless it is immediately supported, nationally celebrated and cherished by society at large.

The landscape is revealed to the viewer as a precursor to introducing each musician, from the highest peaks of Gilgit Baltistan where the instrument Chardha resides, the bustling metropolises of KPK that is home to the Sarinda, to the cultural hub of Lahore, where the 37 stringed Sarangi resonates. All the way from the scorching temperatures of Mohenjo-daro, the ancestral abode of the Boreendo, to the sea where the sound of the Balochi Banjo meets the soothing waves. Places such as Umerkot and Goth Khamiso Khan have been featured, which an average person residing in a local metropolis would have never seen before watching this documentary. The scenery is woven into the narrative seamlessly, as each performance captured during the documentary becomes memorable, pulling at the heart strings of the viewer.

Furthermore, Sharif does not shy away from documenting the difficult subject of abandoning our musical heritage at the hands of uninformed religious viewpoints. The unforgiving attitude and hateful violence of local people against musicians, and at times against Sharif’s own crew while filming, is frightening. Yet, it has not deterred the spirit of these passionate, joyful and devotional musical maestros, sharing their life experiences with Sharif.

Another important aspect explored, is the relationship between the instrument’s maker and player: one of friendship and kinship. Faqeer Zulfikar, the last player of the Boreendo depends on Allahjurriyo Kambar, the last maker of the wind instrument. We feel the intensity of these finite moments, now knowing that this bond is ephemeral. The musical ensembles and troupes talking to us directly from their homes, craft studio and stage, perform only for their small marginalized communities. We join their community and through these performances become sympathetic towards their struggles of survival in this modern era of western musical influences, technology and lack of supportive agencies. These instruments are surreal, with their complex hierarchy of strings and the unique bow, used to play a symphony of notes. It is these sweet-toned chamber instruments made tirelessly by craftsmen that remind us how music is passed down through generations because of its precise tonality and sophistication of notary. It is sound that is indigenous and rooted in our regional identity. It cannot be manufactured or synthesized with the aid of mere software.

We are brought face to face with important questions, such as why are these musicians facing a neglected state of existence? We are compelled to ask ourselves what we can do to help these communities of musicians. A call to action is set into motion by these musicians, who have dedicated their lives to playing instruments that are neither valued nor known to the general public. Surely, it seems our indifference will lead to the demise of these instruments. It is unfortunate that we do not see these musicians as theologians, philosophers and custodians of our cultural heritage. Instead, they have been pushed away and are living on the periphery of our society.

Foundation of Arts, Culture and Education (FACE), and Bipolar Films are the supportive production teams behind Indus Blues. FACE was approached by Sharif, for help with generating funding for this documentary project. Since FACE is non-profit, with the mission of promoting and encouraging independent artists, musicians and film makers with impactful ideas, they began working as close collaborators. Bipolar Films, an Islamabad based film production company, have previously worked with Sharif on the documentary “K2 and the Invisible Footmen.” Their partnership with the German Embassy and USAID has ensured that Indus Blues has become a documentary feature film, with the hope of having a sequel. It has already won the Best Cinematography Award from Pakistan Documentary Feature Film Category at the 11th Jaipur International Film Festival – JIFF, 2019 and the Spotlight Gold Award 2018, and the film seems fully dedicated to bringing positive social change in Pakistan.

Published in: Youlin Magazine

Date Published: June 17, 2019

Review By: Nayha Jehangir Khan