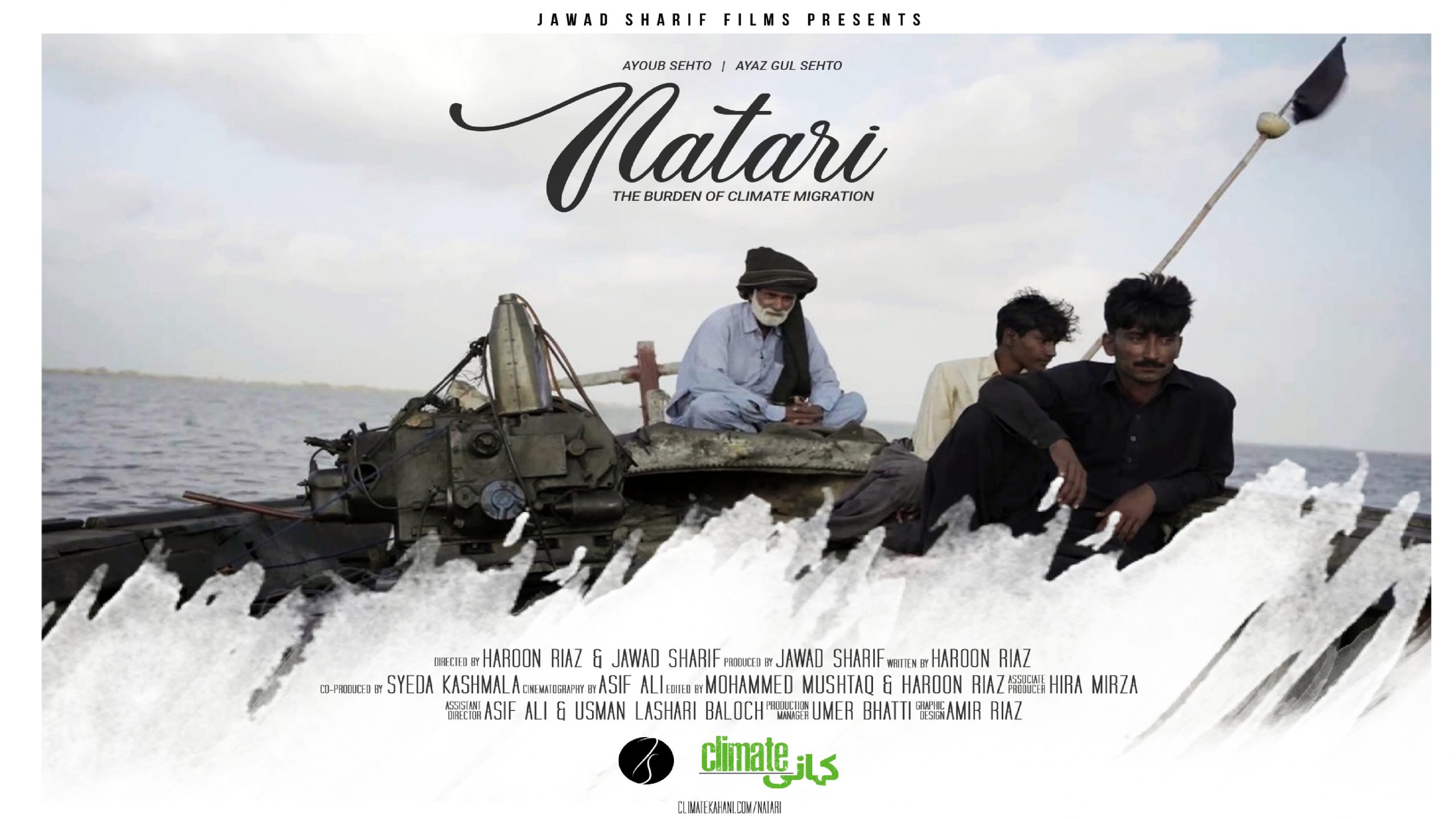

A pale sky reflects onto an empty ocean, creating an endless and desolate landscape interrupted only by the wooden fishing boat of Ayoub Sehto and his son. The colourless palette of Sehto’s world is not how you and I imagine dystopia, yet the world he knows is slipping away, taking with it not just an entire village, but also the marine species and fresh water that sustained it, leaving the land parched. Dystopia is here, and Jawad Sharif and Haroon Riaz’s Natari is its witness statement.

Film Natari (meaning anchor in Sindhi) is part of the official selection of the Climate Crisis Film Festival 2021, being held in line with the COP26 in Glasgow, UK, and online from November 1 to 14. It brings home the issue of climate migration and is a poetic portrait of the helplessness, hard choices and pain of the migrant. Sharif’s filmography in some ways reads like eulogies written on the deathbeds of worlds that are slipping out of our grasp—things that are dying but are worth saving for they are the very essence of who we are. The landscape and social identity always feature large. In Indus Blues (2019), for example, Sharif focuses his lens on the dying musical instruments of Pakistan and the identity crisis engulfing the country.

Sharif has transitioned from commercial television production to non-fictional storytelling to talk about narratives that don’t get space in mainstream media. Concerned with the apathy to the climate crisis in Pakistan, he decided to do what he does best: push for action through films. He has started the Climate Kahani campaign, which focuses on local stories and Natari (45mins) is the first film in this effort. “By adding kahani to climate,” he says. “[W]e wanted to bring it into the local context; we have to communicate in the people’s language.”

He hopes that in Ayoub, a fisherman and activist from Kharo Chan, Pakistanis will be able to see someone like themselves and realise that climate change in not something distant happening in Greece or Australia, but right here, at home as well.

Sharif speaks of the challenges of shooting the film itself in Kharo Chan, which has no electricity or drinking water. In Kharo Chan, which is situated in the Indus Delta region where the fresh water of River Indus meets the Arabian Sea, climate migration and water distribution policies have forced most inhabitants to desert the island.

The slow, lengthy shots that set the pace of the film are a conscious choice; they reflect the helplessness and frustration of Sehto and his son in the face of nature and apathetic state policy. The grass is barely greener on the mainland areas such as Thatta or Karachi. Their fellow villagers who have already fled the impending doom, live alienated, uncomfortable lives as migrants, cut off from their ancestral land and vocation.

The effects of climate change intersect with politics, an oppressive feudal structure and larger state policy on water management which may be choking off the delta and the rich human, marine and vegetative life it sustained. The challenges of taking on the initiative to advocate for climate action are myriad. Among them is the fatalistic attitude of people. “Everything is left up to divine intervention; they say nothing can happen to Pakistan,” says Sharif. He feels such a mindset relieves people of the responsibility to take action themselves. Added to this are bureaucratic challenges. He feels that films like his could be the first step in influencing policy change. But with hard-to-reach ministers, the process is impeded.

Sharif has screened the film locally at universities and private exhibition spaces. The feedback consistently has been that people are unaware of climate migration in Pakistan before they saw the film. This is why Sharif feels that being featured on an international platform such as the Climate Change Film Festival is a great opportunity to shed light on climate in Pakistan. “This could be a first step. My skillset is telling a story authentically… but perhaps someone who sees it can take action,” he says. In the very least, being featured on an international platform means the film has outreach and pressure is built. “We need hundreds of films like this…,” says Sharif. “[P]eople who care need to build a mainstream narrative on climate.”

As an independent filmmaker Sharif faces the same stumbling blocks such as funding and censorship that many others do. While he is fortunate to get commercial work in order to fund his passion projects, censorship is harder to evade. After it took him a year and a half to obtain the censor certificate for Indus Blues, he frankly discusses dwelling on whether to put in the word ‘dam’ in this film. It instantly politicises the issue, becoming a no-go area. He speaks of his frustrations with the censor board: “Non artists judge your art.” Nevertheless, he says is determined to resist the urge to self-censor and continue to express himself on pressing issues of our time.

The Climate Crisis Film Festival’s programming focuses on channelling constructive collective action and providing an intersectional analysis of climate, politics, economics and social justice. Sign up to catch Natari for free until November 14, 2021.